This is a review of my computer vision final project, to restore color to legacy black and white photography. We trained a convolutional neural network (CNN) to colorize grayscale images using a VGG19 U-Net architecture with TensorFlow. The project was called RGBIT and was maintained as a 100% free and open-source application and API to restore color to legacy grayscale photography. A live version of the project can be found here. Contributors to this project include: Tyler Gurth, John Farrell, Hunter Adrian, and Jania Vandevoorde.

GitHub Repository, Live Demo, Research Report

Summary

We sought to create a model architecture and algorithmic process to take grayscale photos, and color them to a high efficacy. Through proper research, we determined that large Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) would be the most proficient in this difficult task. Although often used for recognition and classification, a basic understanding of a CNN is that it takes an input and an output, and tries its best to create weights that make that conversion.

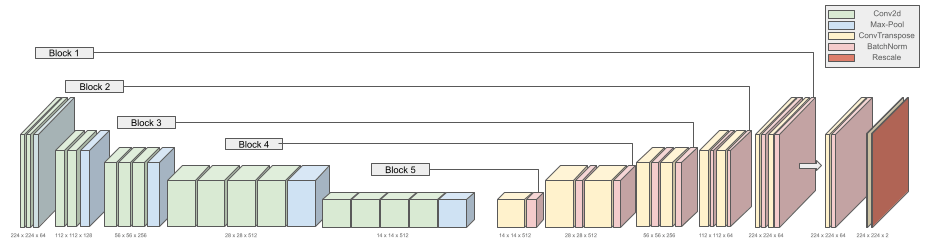

We implemented a convolutional neural network (CNN) to colorize grayscale images using a U-Net architecture with the VGG-19 model. U-Net is a popular deep learning architecture known for its effectiveness in image segmentation tasks. VGG-19 is a large model with almost 150 million parameters that is pre-trained. It is traditionally used for feature detection and was adapted for colorizing in our project. Our model is trained using the MIT Places365 dataset, which contains 365,000 images of scenes (which we split into 328,500 train and 36,500 test images, a 90/10 split). Moreover, the model makes use of a custom Perceptual Loss function for a higher level chromatic evaluation of the CNN. Our results show that the model produces vibrant and realistically colored images. This project reinforces the potential of deep learning in creative image processing. Below is our VGG-19 U-Net architecture.

Methodology

On the simplest level, the goal of this project and our model is to convert a grayscale image to color. In other words, converting a 2d array of light intensities to a more complex array of color values. A naive approach is to use the RGB colorspace. Our model input is a matrix, where and are the dimensions of our image. The output is a matrix, there each channel is an RGB channel. A better approach is to use the LAB colorspace. The L channel represents light intensity, the same as our imput. The A and B channels represent the color values. The A channel represents the green-red axis, and the B channel represents the blue-yellow axis. This is a more intuitive way to represent color, as it separates light intensity from color. Not only does this elimate an axis we must predict, but allows us to rescale the AB channels while maintaining the same light intensity. Another common colorspace for colorization is the LUV colorspace.

Because the pre-trained VGG-19 model expects a matrix as input, we pass as input a 3 channel image of all L channels. In this case, is . The model then predicts the AB channels, . We compare the truth and predicted AB channels using our perceptual loss function, defined in detail in the next section. The model can be summarized as a function .

Using the LAB colorspace allows us to input an image of any size, downscale it to , then upscale to original image quality, as we preserve the light intensity channel. This is a more robust approach than using the RGB colorspace. You can see this in live action on our demo.

Loss Function

Defining a loss function was simple enough, in fact, our naive implementations just used MSE (Mean Squared Error) to calculate the differences between predicted and ground truth channel pairs. That being said, research guided us to define a more complex perceptual loss function, to consider images that had variations, but on a high level, should produce a similar smoothed color scheme. The perceptual loss function prioritizes high-level features over pixel-level differences, which is more in line with how humans perceive color. Our loss function is defined as follows:

We started with the MSE:

We used this MSE as a component for finding what we call a Gaussian Filtered MSE (GD, or Gaussian Distance), (where is the filter size, and is the Gaussian filter function, which also takes a filter size.).

We used our GMSE function at several filter sizes to define our loss function (where, here is the MSE function).

Our loss function acts as a more complex, perceptual function with higher level smoothing, leading to faster convergences due to its somewhat underfitting nature. Although it is less sensitive to small variability, it resulted in smoother (and, more optimized) outputs.

Here is the code blob for our loss function:

def percept_loss_func(self, truth, predicted):

truth_blur_3 = blur(truth, (3,3))

truth_blur_5 = blur(truth, (5,5))

predicted_blur_3 = blur(predicted, (3,3))

predicted_blur_5 = blur(predicted, (5,5))

dist = mse(truth, predicted) ** 0.5

dist_3 = mse(truth_blur_3, predicted_blur_3) ** 0.5

dist_5 = mse(truth_blur_5, predicted_blur_5) ** 0.5

return (dist + dist_3 + dist_5) / 3Results

Our final model achieved a validation mean square error ~135. This is a somewhat arbitrary metric, which compares the true and predicted AB channel difference for each pixel. The model is not meant to perfectly predict original colors, but to create a plausible and natural looking colorization.

The results of perceptual loss showed our model and architecture is viable for creating naturally looking colorful photos, but doesn’t correctly account for unique coloring and saturation. To account for unsaturated colorization, we postprocess the images by increasing the contrast by . Colors returned are plausible and look natural to the human eye. The model can be used to color any grayscale image, but has best use-cases for naturally existing photos, such as old black and white photography or night vision goggles. Below are some example results from our model test dataset. The first image is the L channel, the second image is the truth coloring, and the third image is the predicted coloring.

Results against popular legacy black and white photography. Truth channel is the grayscale image, and the predicted channel is the colorized image.

|

Conclusion

We experimented with using perceptual loss and VGG-19 U-Net architecture to predict the colors of grayscale images. The results of perceptual loss showed our model and architecture is viable for creating naturally looking colorful photos, but doesn’t correctly account for unique coloring and saturation. Colors returned are plausible and look natural to the human eye. An improvement would to be to quantize the colorspace into bins, and use a cross-entropy based loss function, discussed here. Quantizing the colorspace allows us to weight rare colors heavily, reducing the unsaturated color bias.